Long-Range Financial Plan: First Steps

Long-Range Financial Plan: First Steps

We all know Ottawa is a wonderful place to live. Over the past 20 years the city's population has increased more than 40 per cent. Economic growth in cities drives the success of the national economy and creates significant tax revenue for both the federal and provincial governments.

But for Ottawa, and other large cities in Canada, growth brings new challenges - the need for expanded road, water and sewer infrastructure, demand for new cultural and recreational facilities, desire for improved transit, and so on. Right now, cities pay over 80 per cent of the costs of growth infrastructure and receive only 7 per cent of the revenue generated from this growth. Economic and policy experts agree: property taxes can no longer fund the bulk of services that municipalities deliver and, unless stable, long-term funding is secured from the federal and provincial governments, severe limitations will exist on its ability to manage growth.

City Council recognizes the importance of finding innovative ways to improve services and reduce costs, while at the same time, carefully examining and cultivating new sources of revenue. They asked City staff to prepare a Long-Range Financial Plan (LRFP) - a document intended to address these challenges and set out the City's financial outlook over the next ten years.

The first part of the LRFP - Long-Range Financial Plan: First Steps - was approved by City Council on October 23, 2002. As outlined in its executive summary, this document is intended to increase understanding of the challenges the City faces as it grows and provide Council with a number of approaches to consider as they decide how to manage growth and continue to provide high quality services to residents.

The second part of the LRFP will provide a more detailed ten-year forecast. This document will be submitted to Council in late 2003, along with the 2004 draft budget.

Citizens have an important role to play in the discussion of these issues that affect you, your family and your community. So get involved, tell us what you think about the options and alternatives, and have your say.

Overview

During the City of Ottawa's 2002 budget process, a funding gap in the City's capital program was identified. More detailed study was undertaken and this funding gap was forecast to be $270 million by 2006, or approximately $100 million each year from 2004 on. As a result, Council directed staff to prepare a long-range financial plan to outline the City's operating and capital needs, and to recommend strategies to address the funding gap.

In response, this long-range financial plan examines operating and capital needs over a period of ten years (2002-2011), sets out assumptions on which these needs are based, presents existing funding sources, outlines potential new funding sources (both those under Council's control and those which may require decisions of other parties), and recommends actions by which the City can secure a solid financial future.

The long-range financial plan sets out a short-term capital forecast (2002-2006), and a long-term capital forecast (2007-2011). The short-term forecast provides significant detail on projects both anticipated and now underway. The long-term forecast offers reasonable spending estimates by grouping related projects together in spending envelopes. This two-part method has been used because planned projects may be affected over time by many variables, including economic fluctuations, changing growth rates, amendments to legislation and regulations, and further provincial downloading.

Although, this long-range financial plan constitutes a comprehensive examination of the City's capital and operating needs, additional work remains. Next steps will include submission of the draft 2003 budget estimates, an asset management review for transportation, water and wastewater infrastructure, and a final version of the City's Official Plan. A second phase of the long-range financial plan will be developed based on this information and the results of the City's other growth plans (the human services plan, the arts and heritage plan, the economic plan, and the corporate strategic plan). This second report will provide a more detailed ten-year forecast that will be submitted to Council in late 2003, along with the 2004 draft budget estimates.

Picture is becoming clearer

Ottawa is one of the most desirable cities in Canada in which to live. Indeed, over the past 20 years, the City has seen its population grow by a staggering 41.6 per cent. These people, in turn, have propelled significant economic development in the City, particularly in the past five years.

Population growth and economic development, however, have associated costs. As such, the City faces tremendous challenges: how will it continue to grow and thrive, sustain its exemplary quality of life, maintain its physical infrastructure, and be able to address unforeseen needs?

City Services include:

- Transit

- Libraries

- Paratransit

- Roads and sidewalks

- Clean drinking water;

- Wastewater and stormwater removal and treatment;

- Fire protection;

- Police services;

- Garbage removal and recycling;

- Public health;

- Social housing;

- Homes for the aged;

- Recreation and parks;

- Child care;

- Administration of Ontario Works

- Ambulances; and

- Planning, licensing and by-laws.

Amalgamation has placed the City in a stronger position to meet these challenges. Indeed, amalgamation has enabled the City to provide many of its services more efficiently and effectively than ever before. Moreover, savings resulting from amalgamation have allowed the City to absorb significant costs associated with inflation and provincial downloading of services. Equally important, amalgamation affords City staff the opportunity to form a more realistic long-range picture of current and anticipated operating and capital needs than was possible with 12 separate, competing local governments.

The advantages of amalgamation alone, however, have proven insufficient to allow the City to overcome this challenge. Ottawa is not alone in this regard. Other cities in Canada that try to accommodate rapid growth with aging infrastructure share the predicament. Edmonton, for instance, recently revealed that its ten-year capital funding gap is expected to total approximately $3.2 billion, with 58 per cent of that amount ($1.8 billion) directly attributable to population and economic growth. Meanwhile other cities, Toronto among them, are just beginning to assess their long-term needs. In all likelihood, they too will be facing significant funding gaps. Indeed, stories such as the one found in the September 24, 2002 edition of the Calgary Herald entitled "Budget Fears Revealed" appear in the media with increasingly regularity. Over the past decade, cities in Canada have been asked to do more with less.

Over the past decade, cities in Canada have been asked to do more with less.

Canada's cities are unquestionably the economic growth engines of the nation. More than 60 per cent of Canada's total employment growth over the last four years has occurred in just ten urban regions. Population and economic growth in urban areas are critical to the national economy. They create significant tax revenue for both the federal and provincial governments but not, ironically, for the municipalities that drive the growth. Growth creates massive demands on services and infrastructure that cities alone must fund.

A clear consensus has emerged among economic and policy experts that Canada's cities lack the legislative and financial tools needed to generate enough revenue to fund the services and programs they must deliver. Indeed, while federal and provincial governments raise revenue to pay for programs in a number of ways-including personal and corporate income taxes, payroll taxes, sales taxes, corporate taxes, and fuel taxes-municipalities in Ontario are permitted to raise revenue only through property taxes, development charges, and user fees. Moreover, while revenues from income and sales taxes are bolstered during periods of strong economic growth, revenue from property taxes is not.

The City of Ottawa receives an estimated seven cents of every new tax dollar generated here; federal and provincial governments receive the balance.

The figures that underlie the dilemma faced by the City are stark. In 2001, a KPMG study found that, between 1998 and 2000, economic growth in the City generated $753 million in additional tax revenue for the federal and provincial governments yet only $77 million additional revenue for the City itself. Put another way, today, the City receives an estimated seven cents of every new tax dollar generated in Ottawa; the federal and provincial governments receive the balance. Between 1995 and 2001, while federal government revenue across Canada climbed 38 per cent and provincial government revenue rose by 30 per cent, municipal revenue increased by only 14 per cent. For municipalities, this figure constituted a per capita decrease.

Over the past 18 months, several studies have been undertaken to examine the role played by Canada's cities, the challenges they face, and the options available to them. These studies include:

- The Role of Metro Areas in the US Economy, DRI-WEFA, June 2002;

- Canada's Urban Strategy, A Vision for the 21st Century, Prime Minister's Caucus Task Force on Urban Issues, May 2002;

- FCM Annual Meeting, May 2002;

- A Choice Between Investing in Canada's Cities or Disinvesting in Canada's Future, TD Economics, April 2002;

- Municipal Finance and the Pattern of Urban Growth, CD Howe Institute, February 2002;

- Communities in an Urban Century, Symposium Report, FCM, January 2002;

- Early Warning: Will Canadian Cities Compete, Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM), May 2001; and

- Towards a Partnership to Invest in Economic Growth: Ontario and Federal Government Tax Revenues from the City of Ottawa, KPMG, February 2001.

Program expenses and physical infrastructure costs that benefit the national economy are borne primarily by municipalities.

In recognizing that most of Canada's economic activity takes place in urban areas, these studies agree that Canada's cities must have the programs and physical infrastructure in place to sustain the population growth and development that comes from increased economic activity. Moreover, social programs and physical infrastructure are critical to strengthening overall national competitiveness. At this point in our history, the costs associated with these programs and with infrastructure development are borne primarily by municipalities. Increasingly, however, it is becoming clear that municipalities lack the stable funding, necessary authority and financial flexibility to fund these requirements alone.

In order to sustain growth and deal with the effects of federal and provincial downloading, municipalities throughout Canada have employed several short-term financial strategies to address the needs of their citizens. These strategies have included drastically reduced funding of infrastructure maintenance, depletion of reserve funds, delayed construction of required infrastructure, use of one-time revenues, operating costs charged to capital, and conservatively estimated operating costs. Indeed, the TD Economics report graphically conveys the predicament faced by Canada's municipalities:

Hit by the double whammy of weak revenue growth and downloading of services, it is hardly surprising that municipal governments have had to run up debt, defer infrastructure projects, draw down reserves, sell assets and cut services in order to stay afloat.

Overview of Ottawa's situation

As more and more experts agree that with no change in the current distribution of revenue and authority among federal, provincial and municipal levels of government, cities cannot sustain growth, it is also clear that the City of Ottawa must continue to find solutions in areas it controls.

Recognizing the challenges faced by taxpayers, the 12 former municipalities that became the new City of Ottawa had frozen or reduced property taxes and rates for a number of years prior to 2001. Faced with revenues growing at a slower rate than the services they fund, municipalities in the Ottawa region continuously improved their methods of providing service while reducing expenditures. Following amalgamation, in 2001, the tax rate was cut by ten per cent; this rate cut was maintained in 2002. The freezes and cut in rates meant absorbing both the cost of inflation and the cost of downloaded provincial responsibilities; the costs of downloading alone have added over $50 million per year to the City's budget.

As a result of the property tax rate freeze, when adjusted for inflation, the average urban resident now pays 20.5 per cent less in property taxes than in 1993, and the average rural resident pays 21.9 per cent less. (see Chart below).

During this period, Ottawa has been one of the fastest growing cities in Canada. To examine potential solutions and plan for long-term growth, therefore, Council adopted a realistic forecast that clearly recognizes current growth rates and increases physical infrastructure requirements. In the past, growth had led to traditional suburban development that was matched by increasing demand for lower density, largely car-based infrastructure. Indeed, this type of infrastructure demand has been responsible for a significant portion of the present capital infrastructure gap. This demand is forecast to increase as the long-range financial plan moves toward 2011.

The City must adopt a more sustainable approach to development and growth.

As a result, the City must recognize that it cannot afford to continue to subsidize development and growth as it has done in the past. The City must reconsider where development takes place, as well as its true cost. In turn, ways must be found to recoup a portion of the City's funding shortfall by changing the way in which the City develops. It should be noted here that a substantial portion of the costs of growth in the City has been subsidized by property taxpayers.

Lifecycle maintenance of existing physical infrastructure-roads, bridges, pipes, and buildings-also presents a unique challenge. Historically, resources sufficient to maintain physical infrastructure have not been included in forecasts and planning. This situation is, in fact, common to municipalities throughout the country. Again, the recent report by TD Economics provides the underlying figures:

The Association of Consulting Engineers of Canada (ACEC) estimated that the total municipal infrastructure shortfall in Canada is at least $44 billion ... TD Economics estimates that the total infrastructure shortfall is growing by about $2 billion per year.

Although all available tools are being examined to determine the ideal way to address the City's capital and operating needs, every city in Canada requires more flexibility to generate revenue. Further, stable funding arrangements with federal and provincial governments are critical if cities are to enjoy long-term financial health and economic growth.

The City is meeting its challenges directly and with foresight. While continuing to improve ways to provide service while reducing expenditures, finding greater efficiencies in service delivery alone will not be enough to close the funding gap. The challenge for the City between now and 2011 will be to continue to find innovative ways to improve services and reduce costs and, at the same time, carefully examine and cultivate new sources of revenue. Without these new sources of additional revenue, and despite the City's best efforts, the funding gap will only continue to grow.

Ottawa is part of a bigger picture

Cities have always been centres of economic activity and growth. With the advent of free trade, cities have become key drivers of national economies, and investments in urban infrastructure provide significant benefits to communities beyond urban boundaries. Indeed, The Role of Metro Areas in the US Economy notes that the gross product of the five largest metropolitan areas in the United States ($1.68 trillion) outperformed every national economy in the world except for the United States ($10.21 trillion), Japan ($4.15 trillion) and Germany ($1.85 trillion). Within the United States, the gross product of the ten largest American metropolitan areas exceeded the output of the 31 smallest states.

This renewed vitality of the world's cities is exciting for those who live there, and rewarding for all those who benefit from their productivity. A general consensus is emerging of which factors allow cities to compete successfully in the global marketplace while being desirable places in which to live and work. Seizing the initiative, national governments in the United States and Europe have made major investments to ensure their cities continue to thrive. Canada's federal and provincial governments have not yet recognized that they must make similar investments if Canadian cities are to compete and prosper.

4.1. 19th Century Solutions Can't Solve 21st Century Problems

In 1867, Canada was largely a rural country with a resource-based economy. Since Confederation, the Canadian economy has diversified significantly. Moreover, Canada is now an overwhelmingly urban nation. Indeed, nearly 80 per cent of Canadians live in urban areas, with 45 per cent of them living in the country's seven largest cities (Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, Ottawa-Gatineau, Calgary, Edmonton and Winnipeg).

Although Canada has undergone radical change over the course of the last 135 years, the statutory mechanisms regulating affairs between federal and provincial governments and their municipal counterparts have not. Indeed, in Canada's founding statute, the Constitution Act of 1867, provinces were given complete control over municipal institutions. In turn, the role, function and structure of these municipal institutions were set out some 20 years prior to Confederation. In 1867-135 years ago-this seemed an appropriate arrangement. Today, it is no longer viable.

Municipalities in Canada have only three ways to raise revenue: property taxes, development charges and user fees.

The current legal framework within which municipalities operate limits their ability to manage and regulate the programs and services they are responsible for delivering. Essentially, municipalities in Canada have only three ways to raise revenue: property taxes, development charges and user fees. Due to their limited flexibility, these ways are insufficient to meet the City's need for additional revenue.

This is not the case in the United States and Europe, where considerable effort has been made to give cities the necessary supports to become and remain successful. In the United States, local governments are granted powers by their state.

American cities can determine which services they will provide, and raise the necessary revenues.

Home rule charters, however, also govern larger municipalities in the United States, and many of the smaller ones. These charters allow cities to determine themselves how they should be organized, what services they should deliver, and to what extent local matters should be regulated-all with no interference from the state. These charters also give cities authority to determine revenue sources, set tax rates, levy new taxes, borrow funds and use any number of other financial instruments at their disposal. As a result, American cities can determine which services they will provide, and raise the necessary revenues (see Table 1).

In Europe, services offered by local governments vary greatly, as does the authority of these governments. Throughout Europe, however, a strong understanding has developed of the important role cities play as centres of economic growth and employment. This understanding is expressed in the principle of subsidiary, which is embedded in the European Union's Treaty of Maastricht. This principle formally recognizes that higher levels of government should exercise authority only when there are obvious and compelling reasons to do so. Subsidiarity also decrees that the level of government that has authority should have the resources needed to meet its responsibilities. The European Union, for instance, offers access to funding that allows local governments to leverage additional financing from their host countries for projects that support sustainable development in the broadest sense-environmental, social and economic.

The practical effect of this difference in defining authority and access to revenue is noteworthy. The Federation of Canadian Municipalities estimates that, in 1997, Canadian municipalities spent $785US per capita, while American cities spent $1,652US and European cities averaged $2,100US.

Some provincial governments in Canada have begun to demonstrate an understanding of the importance to municipal governments of having more flexible financial and legislative mechanisms within their reach. The governments of British Columbia, Newfoundland and Labrador, Alberta, Manitoba, Nova Scotia and Quebec have all either given municipalities authority to raise new revenues or transferred to municipalities portions of sales, income and fuel taxes. In some cases, provincial governments have done both. Further, Alberta has given cities natural person powers, which allows Alberta's cities greater flexibility to enter into legal agreements. Perhaps most promising is British Columbia's proposed Community Charter, which will, if enacted, give municipalities clear authority to make decisions and raise new revenues without having to secure provincial approval.

- British Columbia

- Municipalities granted authority to raise new revenues;

- Municipalities receive a portion of provincial sales taxes;

- Greater Vancouver Transit Authority collects gasoline tax, while the province sets the rate; and

- Hotel/motel occupancy tax collected in Vancouver.

- Alberta

- Municipalities granted natural person powers; and

- Calgary and Edmonton receive five cents per litre of provincial fuel tax (to be reduced to 1.2 cents in March 2003).

- Manitoba

- Municipalities granted two per cent of revenues generated from personal income tax and one per cent from corporate income tax;

- Municipalities collect hotel/motel occupancy tax; and

- Business occupancy taxes are mandatory in Winnipeg, optional elsewhere.

- Quebec

- Montreal receives 1.5 cents per litre of provincial fuel tax and $30 vehicle registration fee; and

- Municipalities granted authority to levy land transfer tax.

- Nova Scotia

- Municipalities granted authority to levy land transfer tax.

- Ontario

- Municipalities granted ten spheres of authority and limited natural person powers under the new Municipal Act.

- Newfoundland and Labrador

- Municipalities have received increased authority in taxation, administration and financial management.

Although progress underway throughout the country is welcome, the fundamental constitutional framework governing municipalities has not changed. The provinces continue to retain control of the legislative and taxing powers of local governments, and provincial governments can restrict or change any previously granted powers at any time. Alberta, for instance, has unilaterally reduced Calgary and Edmonton's share of the fuel tax from 5 cents to 1.2 cents, effective March 2003. The future progress and stability of Canada's cities is threatened by an absence of authority over the services they are responsible for delivering, as well as a lack of stable funding mechanisms to support these services.

4.2 Infrastructure Investments Are Critical to Canada's Economic Success

According to United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan, the world has entered the "urban millennium." In the urban millennium, a nation's cities must thrive globally if that nation is to compete economically. Cities are also expected to be centres of innovation and education, and they must provide the highest possible quality of life to residents.

To that end, the United States and Europe have been making large-scale investments in municipal infrastructure. In Europe, infrastructure funding comes from the European Union, national and local governments, and public-private partnerships. At $175 billion US, the 2002-2006 European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) makes up one-third of the entire European Union budget. ERDF is available to any city or region that can demonstrate both a need and the availability of matching funds within the host country. In recognition of the importance of transportation infrastructure, over one-half of ERDF funds are targeted for these projects. Some one-third is targeted for environmental and water projects. ERDF is just one of a number of funds available to support the strengthening of municipal infrastructure. Other funds provide funding for a wide variety of infrastructure and redevelopment projects.

The United States federal government is also making impressive investments in urban infrastructure. The Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century of 1999 has earmarked $217 billion US for transportation infrastructure over six years. Of this total, over $100 billion US has been made available for public transportation. Further, the act enshrines a transit benefit tax to help level the playing field between parking benefits and transit/carpooling benefits. The act also allows cities to leverage federal resources to encourage private-sector involvement, including direct credit assistance, such as loans, loan guarantees and lines of credit from the Department of Transport for up to one-third of project costs. Finally, the act permits toll revenue credits, where revenues from roads and public bridges count as matching funds for federal grants for other modes of transportation, such as transit. A number of other federal grant and loan programs (listed in Appendix 2.2) provide stable, long-term funding for wastewater, drinking water, housing, and community development projects in American cities.

The approach undertaken in Europe and the United States is paying off. In January 2001, the 2nd Report on Economic and Social Cohesion to the European Commission concluded that reinvestment in cities was an effective means of mobilizing private capital and loans, and led to increased competitiveness and productivity of urban regions. The Role of Metro Areas in the US Economy notes that American cities' ability to compete in the global marketplace is largely due to the benefits of renewed infrastructure. Indeed, unlike other parts of the American economy, metropolitan areas continued to grow during the recent recession.

In Europe, national contributions to public transportation are also substantial. European G8 member nations fund between 15 and 30 per cent of operating costs and between 30 and 100 per cent of capital expenditures. In the United States, the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century is the largest infrastructure investment program in that country. Under the act, combined state and federal funds cover 25 per cent of operating costs and 54 per cent of capital expenditures for public transit. Moreover, the United States and European countries employ a range of innovative financing strategies to fund transportation infrastructure. These strategies include direct credit, toll revenue credits, joint development of transit assets, transport contribution taxes and toll ring roads.

American and European governments have recognized the critical role transportation infrastructure plays in serving as the backbone of every large city's economy. Transportation infrastructure is a considerable expense for government, but it pays off in both ease of commercial activity and development of a high quality of life that attracts businesses and residents.

In contrast, investment in infrastructure by Canada's federal and provincial governments has been declining. Further, transfer payments and grants that remain tend to be conditional, shorter term and project-based. Moreover, the conditional nature of these programs directs funding to eligible projects, which are not necessarily the most urgent or important priorities of local governments.

The Association of Municipalities of Ontario summarized the situation facing Ontario's municipalities in its 2000 Municipal Councillors' Guide:

What a difference a decade makes! The Ontario Grant Reforms Committee of the late 1970s had identified almost 90 different grant programs … The number of different grant programs had reached 100 by the end of the late 1980s. Today, apart from the possibility of temporary transitional funding, and occasional special financial assistance, municipalities receive essentially one annual grant, the Community Reinvestment Fund.

In the case of transportation infrastructure, Canada is the only G8 country without a national urban transit investment fund. In fact, Alberta, British Columbia and Quebec are the only governments in Canada that provide ongoing support for public transit, although other provinces like Ontario have begun new grant programs. The Canadian Urban Transit Association estimates that a $9.2 billion capital investment over five years is required for public transportation. The Federation of Canadian Municipalities estimates the United States invests in urban transportation at more than 100 times the rate of the Canadian government.

The United States invests in urban transportation

at more than 100 times the rate of the Government of Canada.

The figures are equally revealing when transfers to municipal governments are examined. Combined transfers from both state and federal governments in the United States accounts for 27 per cent of all municipal revenues; in Europe, these transfers total 31 per cent; in Canada, combined transfers from federal and provincial governments accounts for 18.7 per cent of municipal revenues. In the case of Ontario, funding is almost exclusively related to income maintenance programs, which are cost-shared between the province and the property tax base.

Some signs have appeared recently to indicate that governments in Canada are, at a minimum, contemplating the funding challenges faced by municipalities. The Prime Minister's Task Force on Urban Issues recognized in its April 2002 Interim Report that Canada's cities require, "a new approach that includes stable federal funding for urban infrastructure programs and funding for projects that clearly exceed the fiscal capabilities of municipal governments."

Constructive action must now follow these words. For until municipalities are granted both the authority and the tools they need to secure stable, long-term funding, they will be unable to manage the demands of urban growth.

4.3 Shifting the Cost Burden

In 1998, the Government of Ontario instituted Local Services Realignment (LSR), otherwise known as downloading. Originally projected to be revenue neutral, LSR saw municipalities assume greater responsibility for a number of key services, including public transit, police, property assessment services, septic system inspection, social housing, and land ambulances.

In practice, LSR has not been revenue neutral. Instead, it has imposed a heavy financial burden on municipal governments throughout the province. For instance, as a result of LSR, the City now must spend an estimated $50 million more each and every year. This cost burden is increasing and is expected to continue to increase over the next ten years, as growing demands are made on services and as more services are downloaded.

Ontario is the only Canadian province that requires

municipalities to fund significant health and social services

programs on a property tax base.

In addition, Ontario is the only Canadian province that requires municipalities to fund significant health and social services programs on a property tax base. While Ontario controls and mandates a great number of social and health programs, it continues to require that costs of these programs be shared by municipalities and funded through property taxes. These programs include public health, employment and financial assistance, childcare and social housing. Meanwhile, other provinces have abandoned this requirement, allowing the property tax base to support those programs for which municipalities have direct responsibility.

In 2002, $186.2 million was required from the City's property tax base to pay for health and social services programs downloaded from the provincial government.

Cost-shared health and social services add significant pressures to the property tax base. In 2002, $186.2 million was required from the City's property tax base to fund health and social services programs. These programs represent 23 per cent of the City's total tax requirement. If the province of Ontario treated health and social services funding the way other Canadian provinces do rather than funding them from the property tax base, the money freed up could be re-directed to reserves, and the capital funding gap in Ottawa nearly eliminated.

Other than capital grants, operating transfers from the Government of Ontario have declined from $493 million in 1995 to $272 million in 2002 (see Chart 3). This decline has had a significant impact on municipal revenue. As well, some federal grants designed to help programs municipalities deliver end up being used by provincial governments on unrelated expenditures. When expressed as a percentage of the City's gross revenue, these transfers have fallen from 31 to 15 per cent. The rate of decline has been a precipitous 9.1 per cent per year.

City's capital funding requirement

5.1 Capital Expenditure Categories

Capital expenditures are made to purchase, develop and renovate assets that support City services and whose lives extend beyond one year. Anticipated spending on these services forms the City's capital funding requirement.

Projects related to the treatment and delivery of drinking water are funded through the Water Fund. Projects related to the collection and treatment of sanitary and storm sewage are funded through the Sewer Fund. The City's water and sewer utilities charge user fees intended to cover the full costs of these utilities. All other projects are funded through property taxes. Currently, taxes are collected through the city-wide levy and urban and rural transit levies. Other revenues, such as development charges and grants, reduce the City's funding requirement from the aforementioned revenue sources.

Capital expenditures are grouped into four categories: lifecycle maintenance (to care for existing assets); and growth (to support new residents and businesses), which form the bulk of the requirement, and ongoing programs (to address ongoing community priorities) and new initiatives (to fund new programs and assets that are not growth related).

5.1.1 Ongoing Programs

Ongoing programs are determined by community needs not characterized as lifecycle or growth related. Generally, these programs-like community-related facilities, affordable housing, new street or park pathway lighting, sports field development, and park and intersection improvements-consist of annual allotments that gradually increase the level of service throughout the City and are an important part of the City's day-to-day service delivery to residents. Also included in this category is planning work-such as the Official Plan and master plans-performed on a cyclical basis. These programs are generally paid through taxes and utility rates.

5.1.2 New Initiatives

New initiatives are large one-time projects that provide a new or improved level of service. Examples could include new transit initiatives, a new library branch, and expansion of the ambulance fleet that are driven by improving service to existing residents rather than by growth. Generally, these initiatives are funded through taxes and utility rates.

5.1.3 Lifecycle Maintenance

The City's physical assets have a total estimated value of some $20 billion. These assets include roads and sewer infrastructure, sidewalks, water, fleet equipment, information technology, parks and buildings. To protect its investment and ensure the economical, efficient and effective performance of these assets, the City must perform appropriate maintenance and repair, along with the timely replacement of key components. This long-range financial plan identifies the estimated level of expenditure needed to address ongoing needs of these physical assets, as well as the impact of deferred maintenance activity. Generally, lifecycle maintenance is funded from the property tax base or the water and sewer surcharge rate base.

Over the past number of years, local municipalities have been unable to make all investments necessary to maintain their infrastructure. Most local governments across Canada were confronted by this situation; often, few options were available to municipal councils and staff. Although past decisions to underfund asset maintenance and repair of assets may have been made out of financial necessity, these decisions have resulted in a significant list of deferred maintenance work.

Accumulated deferred maintenance has a cost. Major physical infrastructure failure can lead to sizeable downtime, increased costs to local business, and impacts the City's ability to serve residents and attract industry. Deferred maintenance also carries associated health and public safety risks, higher utility consumption and other operating costs, and a higher number of unforeseen repairs and replacement work. It may also lead to the need to close a facility, as happened with the Plant Bath, thereby reducing service levels.

Significant capital expenditures are now required to ensure the City's property and other assets are maintained at acceptable levels. Outlined below are each of the City's major functional areas responsible for lifecycle maintenance.

Properties and Facilities Real Property Asset Management is responsible for all of the City's 1024 structures, furniture and related equipment, as well as other real property. Due to the size and complexity of the City's asset mix, lifecycle expenditure requirements are best described by average spending level based on overall facility value.

A number of guidelines for facility renewal funding have been established by professional organizations. The American Public Works Association has published guidelines allocating a minimum two to four per cent of current facility replacement value to provide for facilities renewal. The Society for College and University Planning, National Association of College and University Business Officers, and Association of Physical Plant Administrators of Universities and Colleges recommend 1.5 to 2.5 per cent of replacement value to keep facilities in proper condition for their present use.

City staff recommend calculating the building asset renewal program on the basis of a conservative 1.5 per cent of the replacement value of renewable building infrastructure, which is approximately 80 per cent of the total replacement value of the City's building portfolio. City staff estimates an accumulated deferred maintenance amount of $31 million for the entire building portfolio, and, if funded at the forecast level, the accumulated deferred maintenance obligation will be eliminated by 2011 (see Appendix 4.1). Other options include reducing the number of facilities through disposal. The Corporate Accommodation Master Plan currently underway will investigate the possibilities of this approach for the City's administrative space requirements.

Fleet The City's Fleet branch is responsible for all City vehicles, including fire vehicles, ambulances and buses. As City vehicles age, maintenance costs increase while resale value and reliability decrease. Consequently, Fleet branch must determine an optimum economic replacement point for each vehicle where vehicle replacement becomes a superior option to repair or refurbishment. A variety of factors determine a vehicle's economic replacement point, including maintenance costs, depreciation, downtime, operational impacts, obsolescence, support costs, residual value, reliability and subsidization.

Standard life expectancies vary according to vehicle type and use. For example, the daily routine of waste collection trucks results in shorter lives for these trucks compared with trucks equipped with dump bodies or salt spreaders, which have a more limited use. Each City vehicle has an assigned life expectancy. (These vehicle life expectancies are listed in Table 2.)

| Component | Life Expectancy (Years) | Current Average Retirement Age (Years) |

| Transit Buses | 16 | 26.6 |

| Fire Apparatus | 15 | 23.3 |

| Ambulances | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| Heavy Fleet | 10 | 14.5 |

| Light Fleet | 7 | 12.4 |

As can be seen, many City vehicles exceed their expected lifecycle age. The City's fleet vehicle replacement capital plan was developed to identify long-term, capital funding requirements to replace City vehicles. This plan was prepared by phasing these spending requirements into the recommended spending plans between 2007 and 2011 to achieve economic life standards by 2011.

A recent review of City fleet maintenance costs for vehicles that exceed their scheduled lives showed maintenance costs 23 to 37 per cent above those costs for vehicles within their scheduled lives. Assuming maintenance costs of 30 per cent for over-age vehicles, and an annual fleet maintenance budget of $12 million, the City incurs additional annual maintenance costs of $1.3 million for over-age vehicles. For the City's transit fleet, maintenance and refurbishing costs on over-age vehicles is $2 million each year. These additional costs must be added to fleet budgets until a steady state is reached in 2011.

Information Technology Information Technology (IT) provides key work tools and solutions to all City departments, and is recognized as an essential cost-saving business tool. As such, provision of reliable and effective technology infrastructure and support for corporate systems is vital to City business operations.

Information Technology assets include physical hardware, intellectual property (software), and information (data stored electronically). A number of research organizations provide industry best practices and benchmarks with respect to depreciation and replacement. Combined with analysis and research provided by IT managers, based on professional experience, historical trends and municipal practices, these benchmarks offer a solid lifecycle maintenance schedule.

Computer hardware and associated infrastructure is replaced either when it no longer functions to acceptable performance standards or when new versions of software will not function.

Computer software is also subject to regular maintenance (installation of patches or fixes), upgrades (new releases), and eventual replacement. Software must be replaced either when it is no longer supported by the vendor or when software no longer functions on available hardware.

IT infrastructure and software replacement is dependent on asset type and technological development. For example, desktop computers are typically replaced on a three-to-four-year cycle. Network servers, on the other hand, typically have a longer useful life span, due to their function and assuming proper preventive maintenance has been performed. Industry best practices suggest a six-to-eight-year replacement cycle.

Submissions to the City's 2002-2006 IT capital budget reflect current standards and qualitative measures. New standards are proposed to be phased in starting in 2007, and will be fully implemented by 2011.

Transportation, Waste Diversion, Water and Sewer Infrastructure Transportation, Utilities and Public Works is responsible for lifecycle maintenance of all of the City's physical infrastructure, including transportation systems, pipes, treatment plants, and landfill sites.

The American Public Works Association, American Water Works Association, Transportation Association of Canada, and Federation of Canadian Municipalities-to name a few-have all undertaken a number of studies to develop effective rehabilitation and replacement strategies for physical infrastructure. As a result of these studies, it is apparent that the City needs to use a rehabilitation and replacement methodology with enough sophistication to address specific complexities in infrastructure sustainability. This methodology will have to look at changes in material types, construction techniques, long-term service level requirements, environmental considerations, and the special requirements of buried infrastructure. Further, construction of infrastructure has been undertaken during periods of sporadic growth, resulting in age-wave effects on infrastructure instead of demands for consistent rehabilitation.

Sidewalks, Transit, Roads and Bridges

The City's transportation network is comprised of 1,415 kilometres of sidewalks, 60 kilometres of transitway, 5,200 centreline kilometres of roads, and 95 bridges-the majority of which is in good condition. Preventative maintenance needs, however, are substantially underfunded, to the point that current expenditure levels are approximately two-thirds of what is required. Accordingly, the City's deferred maintenance inventory is growing quickly. An inability to perform rehabilitative work in a timely fashion also leads to a substantial increase in funding requirements to undertake more expensive reconstruction. Budget forecasts identify future reductions to this funding gap. It is estimated that appropriate lifecycle funding levels will be achieved in 2008 and then maintained for the remainder of the forecast period.

Water, Waste Water and Storm Drainage

The City operates and maintains 2,550 kilometres of water mains, providing potable water from two treatment plants, which are supported by 13 storage facilities and 14 pumping stations.

The City has 2,050 kilometres of sanitary and combined sewers with 57 lift stations carrying flows to the Robert O. Pickard Environmental Centre for primary and secondary treatment. Storm drainage is provided by a sewer network totalling 1,825 kilometres in length, with 101 stormwater detention facilities, as well as ditches-mostly roadside-totalling 8,000 kilometres.

Generally, water and sewer networks enjoy a long lifecycle. These networks are composed of a variety of materials to different standards. With several notable exceptions, the City's water and sewer networks are in good operating condition. Hydraulic needs are, however, much greater. Addressing these deficiencies drives much of the prioritization of rehabilitation/reconstruction needs. These needs are addressed through sewer separation, capacity improvements, and work to address basement flooding issues for sewers, and capacity and service issues for water mains.

The City's water and sewer needs are comparable to those in other North American cities; however, current capital spending levels are not adequate-again resulting in a growing gap between needs and rehabilitation activities. Although major initiatives are being undertaken to forecast funding needs, straightforward depreciation forecasts indicate essential network funding levels will be reached by 2008 and then maintained for the remainder of the forecast period.

5.1.4 Growth

New residents and businesses require either new or expanded municipal infrastructure to service their needs. For the purposes of this long-range financial plan, this kind of infrastructure is known as growth infrastructure. Although driven by growth, these infrastructure projects often benefit existing residents. For example, if the City standard is one ice rink for a specified number of people, when the population grows, the City will require a proportionate number of new ice rinks. Since all residents profit from these projects, they are funded both by development charges and by property taxes and utility rates.

Ottawa 20/20 and Charting a Course Ottawa 20/20 is the City's initiative to manage the growth it will experience over the next two decades. This initiative began in June 2001 with the Ottawa 20/20 Smart Growth Summit, where citizens heard from national and international experts and each other in an effort to become familiar with sustainable development principles. Ottawa 20/20 strives to protect and build on a quality of life that the City's residents value.

Five growth management plans are now being prepared: the City's Official Plan, a human services plan, an arts and heritage plan, an economic plan, and a corporate strategic plan. Findings of these plans will be reflected in future capital budgets and form the basis of the next steps for the City's long-range financial plan.

The Official Plan A preliminary draft Official Plan was tabled with the City's planning and development committee on June 27, 2002. Tabling the plan initiated a public consultation process that will continue well into the autumn of this year, culminating with a final draft Official Plan in January 2003. Following a second public consultation period, Council will adopt the Official Plan in the spring of 2003.

The Official Plan will be supported by several other plans, including a transportation master plan, an environmental strategy, and water, wastewater, and stormwater master plans, which, where possible, will be developed concurrently with the Official Plan.

Although the preliminary draft Official Plan covers a spectrum of growth management goals for the next twenty years, a number of these goals, and related policies, will have a direct bearing on the City's attempt to lessen capital budget pressures. These goals include promoting walking, cycling and transit as viable alternatives to automobiles, supporting development within existing urban and village boundaries, and increasing development densities near transitway stations, along arterial roads, and on main streets. If the goals of these plans are achieved, long-term capital budget pressures on the City can be reduced.

If the goals of the City's growth plans are

achieved, capital budget pressures can be reduced by 2011.

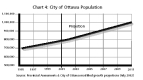

Growth Forecast To plan for growth, the City must know how quickly growth will occur. On October 10, 2001, Council adopted a growth forecast that will form the basis of the Official Plan. This forecast was developed based on recent development activity and compared with the 2001 census for consistency. This growth forecast has been used for the long-range financial plan and is reflected in Chart 4 below. The forecast shows a 26 per cent increase in population from 2001 to 2011, from 800,000 to 1,012,000. As noted previously, employment is forecast to grow from 475,000 jobs to 655,000 over the same period, an increase of 38 per cent.

The growth forecast helps determine the demand for physical infrastructure. Stormwater management ponds are built prior to construction of the first houses in a new subdivision. Water treatment plants must be expanded in advance of increased demand. Parks and fire stations are built once residents are in place. Transportation works, including new and expanded roads and transit systems, are determined by the increased travel needs of additional residents.

The present population forecast has the City adding some 400,000 people in the next 20 years. This degree of growth, if accommodated using a traditional suburban development pattern, would be matched by increasing demands for automobile-based infrastructure. This type of infrastructure demand has already generated a significant portion of the capital infrastructure deficit experienced by the City.

Funding transportation infrastructure is one of the major challenges of growth. Currently, the City funds transportation initiatives using both the city-wide levy for roads projects and the transit levy for transit initiatives. This funding practice has been carried over from the former Region. The transit levy now provides funding for new and replacement buses, transit maintenance facilities, transitway rehabilitation and expansion and other capital projects identified with the transit operation. Transit capital funding is collected from within the urban transit area only. In the future, expansion of road and transit networks should be funded from the same tax base.

Transportation solutions should be considered on a city-wide basis recognizing that expansion of both the transit and road networks may be required to form the solution. Extension of the transitway or alternate transit services should be seen as a transportation solution in the same manner as road construction and should be funded from the same tax base.

The urban or rural transit levy should be earmarked for operating and capital requirements of the transit service (such as buses, garages and other services that directly support the operation) within either the urban or rural areas. This approach has already been adopted in the rural service strategy.

The City's capital infrastructure deficit can be reduced by changing the way the City develops. One alternative is investing in high quality transit, which in turn reduces the need to build more arterial roads and expressways. This alternative also provides significant side benefits, such as less air and water pollution, and the creation of high quality community living. Any increase in the share of trips taken by transit reduces infrastructure costs.

Investing in sustainable development saves money.

A 1995 Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation study compared costs of conventional development with those of sustainable development (one with denser development and a broader mix of housing types and land uses) on a 338-hectare site in Nepean. The study showed the total lifecycle (75 years) cost of sustainable development to be 8.8 per cent less than conventional development. Further, more than 70 per cent of these savings were on public utilities, such as roads, stormwater management, transit, water, policing and sanitary sewers. In short, investing in sustainable development rather than conventional development saves money.

First five-year capital budgetary forecast

The first five years (2002-2006) of the ten-year forecast period (2002-2011) have been planned in detail. The five-year forecast is based on the 2002 Capital Budget and Four-Year Forecast adopted by Council in March 2002. Some changes have been made to the Capital Budget and Forecast using the most current information available. Despite this careful planning, the City's budgetary environment is expected to change during this forecast period. These changes will result in revisions to priorities. Projects summarized in Table 3 represent what City staff knows at this time.

Projects have been divided into four categories: lifecycle, growth, ongoing projects, and new initiatives. (Project lists and summaries are included in Appendix 5.) In July 2002, Council directed staff to bring forward a five-per cent overall reduction in the 2003 capital envelope, reducing this envelope to $476 million. Final results of this directive will be included in the draft 2003 budget submission.

| Category | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | Total |

| $M | $M | $M | $M | $M | $M | |

| Lifecycle | 232 | 254 | 308 | 238 | 248 | 1,280 |

| Growth | 149 | 130 | 216 | 93 | 82 | 670 |

| Ongoing Programs | 35 | 35 | 42 | 40 | 38 | 190 |

| New Initiatives | 105 | 64 | 54 | 58 | 30 | 311 |

| Total | 521 | 483 | 620 | 429 | 398 | 2,451 |

The total of this program exceeds the five-year program in the adopted 2002 Capital Budget and Four-Year Forecast by $42 million. This increase is composed of three major components:

- The Emergency Medical Services Facility is expected to be a public-private partnership. The City's 2002 budget included this project at a zero net cost. In this report, a gross cost of $20 million has been included in expenditures, and P3 funding applied to result in the same net zero capital cost.

- The Southwest Transitway Extension increased by $14 million.

- Park development increased by $6 million.

6.1 Lifecycle Maintenance (2002-2006)

Lifecycle maintenance accounts for 52 per cent of the capital forecast. Expenditures on lifecycle maintenance over the next five years will be determined by affordability. Over time, however, spending levels should increase to a level required to maintain the City's assets. Lifecycle maintenance is divided into five categories: fleet, property and facilities, information technology, transportation and environmental infrastructure, and water and sewer infrastructure.

Fleet From 2002 to 2004, replacing articulated buses will be a priority. Replacement costs should be $24 million in 2002 and $5 million in 2004 (see Appendix 4.2). Spending on other fleet vehicles should increase from $36 million in 2002 to $55 million in 2006, lowering the per centage of over-age vehicles in all classes.

Property and Facilities Spending on property and facilities is forecast to increase from $28 million in 2002 to $38 million by 2006. This increased spending should reduce the deferred maintenance backlog over the short term and eliminate it by 2011.

Information Technology Spending on information technology lifecycle maintenance is forecast to increase from $23 million in 2002 to $28 million in 2006. Appendix 4.3 outlines replacement measures to be implemented from 2002 to 2006.

Transportation and Environmental Infrastructure Spending on transportation infrastructure includes roads, sidewalks, transitways and solid waste facilities. Spending on these programs is forecast to increase from $57 million in 2002 to $67 million in 2006; much of this increase will go to road reconstruction and rehabilitation.

Water and Sewer Infrastructure Water and sewer programs include maintenance of the City's water distribution and collection network and its wastewater treatment system. Some of the essential components of these systems require extensive rehabilitation and are included in upcoming forecasts. Replacement of the 85-year-old transmission mains from the Lemieux Island Water Purification Plant and the Combined Sewer Area Operational Control Tunnel account for $91 million in this period. The control tunnel is an integral component of the combined sewer replacement strategy, needed to satisfy Ministry of Environment requirements. The alternative-continued sewer separation-would cost substantially more.

6.2 Growth (2002-2006)

Growth represents 27 per cent of expenditures over the first five years of the planning period. This figure is based on current needs, official and master plans, and the growth forecast. Spending levels in this category differ significantly from year to year. The 2002 Budget and 2003 Forecast includes many of the SuperBuild projects listed in Appendix 3.1. A substantial spending increase in 2004 is the result of several major projects: a new transit garage to accommodate fleet growth; new pools and ice pads; and transportation projects identified in current plans.

Other growth projects include pipe infrastructure to service urban development and large-scale step-like expansions to water and waste treatment facilities. For instance, a major expansion of water filtration capacity at the Lemieux Island Water Purification Plant is required to meet expected increases in demand. The R. O. Pickard Environmental Centre (ROPEC) also may require expansion. The growth forecast assumes continued use of the Trail Road waste facility, but does not include other waste disposal options should the province deny its approval.

6.3 Ongoing Programs (2002-2006)

Ongoing programs include transportation, utility, and environmental programs. Transportation programs include pedestrian accessibility, cycling facilities, on- and off-street parking facilities, street lighting, traffic management, traffic control and safety, transportation demand management, and transitway improvements. Utility programs include water quality and environmental compliance, flow monitoring, wastewater facilities upgrades, recycling bins, and household special-waste mobile depots.

Programs related to property and facilities include retrofitting for changed uses, and improving efficiency, accessibility and security. Also included in ongoing programs are community-related programs such as park improvements, sports field development, capital partnerships, affordable housing and childcare capital grants.

These programs are forecast to remain at consistent expenditure levels over the first five years of the planning period.

6.4 New Initiatives (2002-2006)

New initiatives are forecast to include: an emergency medical services facility; an emergency medical services advanced-care training program; an emergency and disaster response program; relocation of employment and financial assistance offices; a south-central district library; the police strategic staffing initiative; solid waste management alternatives; and enhanced waste diversion. In 2002 and 2003, specific transition-related projects of $68 million and $15 million are also forecast.

On the water and sewer rate supported side, anticipated regulatory changes over the first five years of the planning period will likely involve major projects like: ROPEC regulatory impacts; water purification plant water-quality improvement program; and water purification plant waste management. In addition, new initiatives resulting from the Safe Drinking Water Act remain unknown.

Year five to year ten capital projections

The specific amounts and timing of capital projects within the 2007 to 2011 capital spending envelopes are not as predictable as the forecasts for earlier in the planning period due to uncertainties of future City priorities. Accordingly, all numbers identified for this period should be treated as illustrative rather than precise. As well, until the Official Plan and its accompanying growth plans are completed, the 2007-2011 forecast has been projected by program rather than by project. Estimated total spending is shown below.

| Category | 2007-2011 Projected | Average Estimated Annual Expenditures |

| $M | $M | |

| Lifecycle | 1,705 | 341 |

| Growth | 1,365 | 273 |

| Ongoing Programs | 293 | 58 |

| New Initiatives | 343 | 69 |

| Total | 3,706 | 741 |

7.1 Lifecycle Maintenance (2007-2011)

The lifecycle maintenance forecast has been designed to eliminate deferred maintenance and show lifecycle expenditures at recommended levels. As such, spending on lifecycle maintenance is shown as increasing from $248 million in 2006 to an average of $341 million each year between 2007 and 2011 to meet these recommended levels.

| Area of Lifecycle Responsibility | 2006 Expenditures | 2007-2011 Average Annual Expenditures |

| $M | $M | |

| Real Property Asset Management Fleet | 29 | 38 |

| Fleet | 55 | 85 |

| Information Technology | 28 | 26 |

| Transportation | 67 | 85 |

| Water and Sewer | 55 | 86 |

| Other | 14 | 21 |

| Total | 248 | 341 |

Deferred maintenance on City properties, facilities and vehicles is expected to be completed by 2011. Deferred maintenance levels for transportation, and water and sewer infrastructure will be included in the long-term strategy for asset management report.

Information technology lifecycle spending levels are forecast to have reached recommended levels by 2006. Lifecycle maintenance levels for transportation, and water and sewer infrastructure are expected to reach their recommended levels by 2007.

A key requirement is the continued refinement of integrated management techniques and resulting programs to ensure appropriate rehabilitation is undertaken both for linear assets and potable water and stormwater and wastewater treatment facilities. These techniques and programs form the basis of asset management reviews now underway. Based on a straightforward value analysis, therefore, 2007-2011 values provide a realistic attempt to forecast necessary funding to meet lifecycle needs commencing in 2008.

7.2 Growth (2007-2011)

Growth requirements between 2007 and 2011 will be speculative until the City has a new Official Plan. Where and how growth will take place has not yet been determined.

The City's capital forecast assumes the new Official Plan will allow the City to promote less capital-intensive growth. Any potential savings from this approach are anticipated to accrue to the transportation envelope of funds. Notwithstanding any savings, a significant requirement is expected to exist for infrastructure to support projected urban growth. The total estimate for growth is $1.365 billion for 2007 to 2011 compared to $670 million for 2002 to 2006.

The capital forecast assumes new facilities would be provided to maintain existing per capita levels of facility space. Facilities include pools, arenas, community centres, parks, cultural facilities and libraries. Other growth-related infrastructure projects and priorities will become clearer as the growth plans are adopted by Council.

7.3 Ongoing Programs (2007-2011)

Expenditure levels for ongoing programs are expected to increase between 2007 and 2011, and new program types may be added. Spending on community-related programs is estimated to increase from $10 million in 2006 to an average of $20 million each year between 2007 and 2011. Transportation programs, such as area traffic management and intersection improvements, are expected to increase from $14 million in 2006 to $20 million each year from 2007 and 2011. Expenditures on property and facilities programs are expected to increase from $9 million to $11 million. All program increases are projected in response to anticipated community needs.

7.4 New Initiatives (2007-2011)

Tax-supported new initiatives decrease from an annual average of $48 million between 2002 and 2006 to $37 million each year between 2007 and 2011. This decrease results from completion of transition projects. Tax-supported programs include projects such as new facilities not driven by growth.

Rate-supported new initiatives will increase from $7 million in 2006 to $30 million each year between 2007 and 2011. Enhancement to the water treatment process using ultraviolet light has been identified in anticipation of more stringent requirements in the future. Also, increased capacity for aeration tanks at ROPEC has been identified. Timing of the aeration tanks may be influenced by provincial regulations. A program for biosolids volume reduction in response to community concerns is included in this period, as well.

Long-range financial planning in water, sewer and waste will continue to be influenced by new and emerging guidelines, standards and regulations. It is expected that regulatory efforts will continue to move forward to promote environmental and public health. Estimates have been included concerning both water and wastewater treatment plants and any anticipated regulatory changes. The regulatory scope, impact and timing for a number of new items of legislation, however, are not yet known. These variables, therefore, could impact long-range financial requirements.

Where it is not constrained by overriding regulations from the provincial or federal levels of government, costs can also be influenced by policy decisions of Council. Beneficial reuse of biosolids, waste diversion goals, and rural servicing options are examples of issues that may have significant cost impacts.

It is also difficult to anticipate any specific programs that may be downloaded, although experience indicates any new downloaded responsibilities will not come with appropriate revenue streams. As a result, any added responsibilities could also have significant cost impacts.

7.5 Infrastructure Standards

Infrastructure standards drive the cost of projects and the overall capital program. Standards include frequency of major repair or replacement, quality of materials, and design components (functional versus "nice-to-have"). Project estimates include contingencies that vary considerably. These contingencies can represent a significant component of project costs.

Are the City's standards too high? Are its programs too expensive? Are its program costs higher than other comparable municipalities? A review of standards, comparing them with other similar municipalities and taking into account relevant factors, would help answer these questions and assist Council to identify areas of capital program cost reductions.

Future operating budgets

An accurate long-range financial plan includes a thorough analysis of pressures on future operating budgets. A careful examination of operating budgets includes a review of impacts resulting from the implementation of future capital programs, and capital financing required to support future capital programs.

Base Operating Impacts

Over the City's ten-year planning term, City programs and services face a number of funding pressures. First and foremost are inflationary pressures. Each year, the cost of goods and services needed to provide programs and services increases. Inflationary pressures add approximately $24 million annually to the budget. Collective bargaining with City employees will also cause service costs to rise.

The impact of population growth on the operating budget must also be considered. Population growth causes increased demand for services, and translates into a number of new requirements: new roads, streetlights, parks, sidewalks, water mains and sewers, community facilities, recreation programs, new ambulances. As such, population growth and economic development place additional pressure on the City's tax rate. Growth pressures average $10 million per year.

Socio-demographic Trends

Between 2002 and 2011, the City will face many important social and demographic challenges. These challenges include an aging population, increased homelessness, the affordability of housing, and concerns surrounding personal safety and security.

In 2001, 88,000 of the City's population were 65 years of age and over; this figure is expected to rise to 124,000 by 2011, an increase of 40 per cent. As a result of this aging population, the City's health and social services needs will rise at a faster rate than previously experienced.

The City also enjoys greater ethnic diversity as more immigrants from Asia, South America and Europe make the City their home. Moreover, the influx of migrants (people moving from another country or province to the City) is expected to increase threefold over the next ten years-from 7,600 in 2001 to 21,000 in 2011.

Over time, additional outreach services will be required to help integrate these new residents. Furthermore, to keep pace with the City's changing population, services must be tailored to community needs, including increased investments in health and long-term care, recreation and programming for seniors, specialized services for newcomers, and increased community funding for newcomer-serving agencies.

Addressing homelessness and providing adequate access to affordable housing will continue to be significant challenges for the City. A clear and demonstrable need for additional affordable housing-especially rental housing-is evident in the City. As a result of extremely low vacancy rates and a limited supply of new rental units, market rents have risen substantially (see Appendix 1.3). While this has resulted in a backlog of renters already experiencing affordability problems, continued household growth and low construction rates will only exacerbate the problem.

Pressures resulting from the changing face of the City are difficult to estimate, as they will depend on the precise nature of those changes and City Council's direction at the time.

Future Capital Program Impacts

Capital projects often generate additional operating costs. As growth leads to the purchase of additional buses, construction of new community centres, and development of new recreational facilities, for example, so too do these kinds of projects require additional funding to deliver and manage new programs and services, and to maintain and repair new facilities, equipment and vehicles. Based on the projects identified in the City's long-range financial plan, operating costs could increase by over $100 million over the ten-year planning period.

Capital Financing Envelope

Contributions to capital reserve funds, including debt charges, in the 2002 operating budget total $273 million. Decisions surrounding the capital forecast and the pay-as-you-go policy could have an impact on this amount. Current funding levels cannot support the capital programs planned for the next ten years.

Property Tax and Rate Implications

Council reduced the property tax rate in 2001 and froze the rate in 2002, primarily through a combination of amalgamation savings and assessment growth. By 2003, the City's operating budget is forecast to achieve a projected $77 million in amalgamation savings. In 2003, however, amalgamation savings and assessment growth alone will not be sufficient to offset budget pressures. Council will examine the anticipated shortfall during the 2003 budget review process.

City water and sewer operations have also benefited from the efficiencies and savings of amalgamation. Legislative and regulatory changes in the areas of health, safety and environmental concerns, however, increased the costs of providing water and sewer services.

Tax-Supported Projections

Existing tax rates will generate new tax revenue based on assessment growth. From 2001 to 2003, this growth combined with amalgamation savings have enabled the City to absorb a significant amount of inflationary and downloading pressures to achieve Council's budget objectives. In the ensuing years, however, the ability to freeze property taxes at this level will be increasingly difficult given the significant budget pressures discussed in previous sections.

Rate-Supported Projections

Based on expected increased consumption, the amount of annual revenue generated from current water and sewer rates will grow. As with programs funded from property taxes, the ability to maintain future water and sewer rates at current levels will be difficult given projected operating budget pressures and anticipated legislative changes.

City revenue sources

Previous sections have outlined a number of pressures forecast on the City's operating and capital budgets, and capital expenditure requirements over the next ten years. The City's challenge over this ten-year period will be to balance deferred lifecycle maintenance and unmet growth infrastructure needs with a desire for ongoing programs and new initiatives. Expenditure requirements are increasing as well; therefore, revenue sources to fund these requirements must be identified and established.

Property Taxes

The City's major source of revenue is property tax. This revenue includes payments in lieu of taxes paid by other levels of government. The City's property tax base is the value of all property as assessed in accordance with legislation set by the province. The City then sets its property tax rate. Total property taxes are the amount of revenue generated by this rate placed on the value of assessed property. These taxes account for 57 per cent of the City's operating budget, which includes contributions to the City's capital program and debt charges.

Property taxes are an ineffective method for continuing to fund the bulk of services that municipalities deliver.

Most experts agree that property taxes are an ineffective method for continuing to fund the bulk of services municipalities deliver because they:

- Do not necessarily reflect residents' ability to pay;

- Are a poor method of funding income redistribution programs, such as Ontario Works and social housing; and

- Hamper the global competitiveness of municipalities.

Municipalities in Canada do not possess the authority to address the problems associated with property taxes and must, by law, continue to rely on these taxes as a primary source of revenue.

Development Charges

Development charges are fees collected by municipalities, under authority of the Development Charges Act of 1997, to offset capital costs incurred to support growth-related infrastructure. Local governments in Ottawa enacted bylaws under this legislation and established fees based on the services and levels for their respective jurisdictions. Fees apply to all forms of development and are collected when building permits are issued. The City collects $60 million each year through development charges.

Development charges do not recover

growth costs in full.

While available to offset growth costs, development charges do not recover these costs in full. For example, extensions of the City's arterial road network and transit service are constructed primarily to serve the needs of growth areas. These extensions, however, also benefit established areas. As a result, a percentage of these infrastructure costs must be deducted from the total project cost and collected from the existing tax base. This percentage varies from project to project.

Recently, the Regional Development Charges bylaw was amended to address a significant shortfall in the collection of charges for roads and structures infrastructure. A review of the bylaw indicated that, under current rates, a portion of the funding necessary to support the capital program was being collected. An amendment that took effect August 1, 2002 increases rates to allow for collection of an increased share of the total estimated amount of capital required over the 20-year work plan. New revenue for 2002 and 2003 is estimated at $20 million.

Development charges can be used as an incentive to implement Council policy. For example, fees may be waived to support objectives such as development of non-profit housing, mixed-use or intensification at transit stations, and development in downtown and urban growth centres. It is important to note, however, that shortfalls arising from these reductions must be compensated through property taxes.