Introduction

As continual corporations, municipalities keep and manage community wealth, in the form of assets, for generations. They plan for population growth, asset maintenance, demographic changes, emergency preparedness and a host of other eventualities that affect residents' quality of life. As such, they need a longer-term focus than most companies or other organizations. Since amalgamation, Ottawa City Council has recognized the benefits of long-term planning and incorporated this approach into the decision-making process by creating the Long-Range Financial Plans (LRFP) I and II.

Experts agree structural funding issues impede financial sustainability

The first and second LRFPs focused exclusively on planning capital spending. This third edition of the City's Long-Range Financial Plan (LRFP III) is a comprehensive financial document, which also includes operating and capital expenditures and an overview of the City's assets and liabilities.

The first Long-Range Financial Plan, tabled in 2002, examined concerns regarding the financial sustainability of Canadian cities. It summarized findings of major studies on municipal funding, which emphasized the new importance of cities in the global economy, and examined funding differences between major Canadian, European and American cities. The United States government and national governments in Europe are making major investments in their cities and have made numerous funding tools available to municipalities. The Canadian federal and provincial governments' progress in these areas is well behind Europe and the United States.

Successful cities are essential to the success of the modern Canadian economy

Since 2002, a number of other studies have confirmed that serious concerns remain about the sustainability of the fiscal framework under which Canadian municipalities must operate. These studies note that, while the federal and provincial gas tax provides cities with some help in the area of public transit, very little real progress has been made since 2002.

The major conclusions reached by these studies are outlined below.

One of the major economic and cultural shifts that has occurred with the advent of globalization is the emergence of cities as key drivers of national economies. In short, "…cities matter… Indeed, in Canada, as in most other countries, as large cities go so, increasingly, goes the country."1

In Canada, the health of cities is of primary importance to the national economy. It is anticipated that:

as much as 80 per cent of economic and population growth will occur in only six broadly defined city regions: the Greater Toronto Area, Vancouver and the lower mainland, Montréal and its environs, Ottawa-Gatineau, and the Calgary and Edmonton regions."2

While there is no single definition for what makes a successful city, there are commonly agreed upon elements. These include high quality social and quality of life services, first-rate cultural infrastructure, good quality municipal infrastructure, an attractive natural environment, a diverse economy and the ability to attract and retain talented people.

Currently, Canadian cities are internationally recognized as successful. They are highly desirable places to live and work. When compared to American cities, they provide good social and cultural infrastructure and services while offering higher levels of personal security and safety. In 2005, Mercer International rated Ottawa 20th in the world for quality of life, ahead of Montréal and Calgary and most American cities. For cost of living, Ottawa ranked 122nd out of 144, making it less expensive to live in than Toronto, Vancouver, Calgary and Montréal.

However, the continued success of Canadian cities is at risk. The most significant reasons can be summarized as follows:

All of the studies conclude that, while Canadian cities are providing most of the services that lead to economic growth, they do not have adequate financial tools to fund those services. Economic growth increases federal and provincial revenues far more than those of municipalities. This creates a fiscal imbalance for municipalities.

A fiscal imbalance exists when:The fiscal capacity of one order of government is insufficient to sustain its spending responsibilities while the fiscal capacity of another order of government is greater than is needed to sustain its spending obligations, while both orders of government provide public services to the same taxpayer."4

There is a municipal fiscal imbalance that threatens Canada's prosperity

Cities in Canada are creatures of their province. This means that cities do not have control over many of the services they provide and are restricted in their abilities to raise revenues. Cities are subject to the whims of the province in terms of services, service levels and funding. While the current debate in Canada is the federal/provincial fiscal imbalance, most experts agree that the municipal fiscal imbalance is at least as important if not more so.

An analysis of the relative expenditures and revenues of the federal, provincial and municipal governments from 1988-20045 reveals the following:

The studies all agree on two key points regarding the municipal fiscal imbalance:

The existing funding framework means Canadian cities are not able to adequately maintain infrastructure

With more than 80% of Canada's population living in cities, and the vast majority of its businesses centred there, investments in high-quality infrastructure are vital to Canada's economic success. Specifically, the availability and quality of services provided by local infrastructure - water, sewers, solid waste facilities, public transit and transportation systems, cultural and recreational facilities - are critical factors in improving economic growth, productivity and international competitiveness.7

Ottawa's first Long-Range Financial Plan examined the importance of municipal infrastructure, and identified the significant differences between the large-scale investments made by Europe and the United States in municipal infrastructure as compared with Canada's investments.

There is agreement that there is a significant and growing infrastructure gap in Canada, and that it was largely created when federal and provincial infrastructure funding streams were replaced by ad-hoc infrastructure programming. American and European governments have recognized the critical role infrastructure plays as the backbone of every large city's economy; conversely, investment in infrastructure by Canada's federal and provincial governments has been declining. Canada remains the only G8 country without a national transportation infrastructure program. Moreover, given the limits to municipal funding tools, most municipalities have had little choice but to "systematically [under-invest] in infrastructure, both hard and soft infrastructure (e.g., transportation, roads, water, sewers, recreational facilities, community services, etc.)"8 to balance their budgets and limit their debt.

Statistics Canada estimates the value of Canada's existing public infrastructure at $157 billion.9 A number of recent studies have attempted to measure Canada's infrastructure gap, and estimates range from $60 billion to $125 billion, depending on the infrastructure included and the methodology used.10 Even when the lowest estimate is used, the infrastructure gap is significant and the studies agree that it must be addressed if Canada is to remain internationally competitive. Given that municipalities in Ontario have responsibility for most of the province's physical infrastructure assets (62%, compared to 23% for the province and 15% for the federal government), this gap is a particular challenge for Ontario's two largest cities, Toronto and Ottawa.

The conclusion reached by the studies is clear, and can be best summarized by the following:As municipalities grow and age, attention must be devoted to the expansion or replacement of their capital stock. Water plants and sewage treatment facilities must be enlarged or rehabilitated. Transportation and communications facilities must be updated and extended. Brownfield remediation must be addressed and 'blighted' areas of cities revitalized and redeveloped. The need for increased infrastructure funding in Canadian municipalities has been advocated by the Federation of Canadian Municipalities for some time and more recently, by the mayors of the large cities."11

Municipalities will not be financially sustainable without new funding tools and without authority over the services they provide.

1Slack, Enid and Bird, Richard M. "Cities in Canadian Federalism." Presentation. Conference on Fiscal Relations and Fiscal Conditions. Georgia State University, Atlanta. May 2006.

2Slack, Enid, Bourne, Larry S. and Priston, Heath. "Large Cities Under Stress: Challenges and Opportunities." Report. External Advisory Committee on Cities and Communities. March 3, 2006.

3Slack, Enid and Bird, Richard M. "Cities in Canadian Federalism." Presentation. Conference on Fiscal Relations and Fiscal Conditions. Georgia State University, Atlanta. May 2006.

4Kitchen, Harry M. and Slack, Enid. "Trends in Public Finance in Canada." May 24, 2006.

5Ibid.

6Ibid.

7Government of Canada. Fall 2002. Speech from the Throne.

8Slack, Enid, Bourne, Larry S. and Priston, Heath. "Large Cities Under Stress: Challenges and Opportunities." Report. External Advisory Committee on Cities and Communities. March 3, 2006.

9Research Analysis Division, Infrastructure Canada. "Productivity and Infrastructure: A Preliminary Review of the Literature." August 2006.

10The range varies because each study looks at different parts of the infrastructure and different data. Infrastructure Canada has very recently begun a comprehensive literature review in order to develop a work plan to address existing knowledge gaps about the specific nature of Canada's infrastructure gap.

11Kitchen, Harry M. "Physical Infrastructure and Financing." Research Paper. Panel on the Role of Government in Ontario. December 4, 2003.

- Federal and provincial governments are "in effect downloading some of their deficits to those at the bottom of the fiscal food chain - local governments."3 This has been done in a number of ways: by directly offloading services to municipalities (e.g., provincial highways, ambulance service, social services and social housing); by reducing transfer payments to municipalities (e.g., provincial transfers for public transit); by reducing direct government expenditures in areas that directly impact local areas (e.g., reductions to immigrant services and funding for health supports for low income and disabled people); and by imposing "unfunded mandates", where regulations have increased municipalities' expenditure requirements (e.g., water quality standards).

- To remain competitive in the national and international marketplace, cities must provide state-of-the-art transportation and communications infrastructure, high quality cultural and recreation facilities and programming, and reliable emergency and police services.

- Cities experiencing rapid growth are also experiencing higher costs, due to the high costs of building new infrastructure and of maintaining infrastructure that is under stress from a growing population.

- Increased pressures on the expenditure side have not been balanced by corresponding increases on the revenue side. Canadian cities can only raise revenues through property taxes, user fees and development charges. Unlike sales and income taxes, property taxes do not grow with the economy.

- While its revenues have been increasing, the federal government's expenditures, per capita, have been declining. Provincial/territorial government expenditures have been increasing at a lower rate than revenues. Municipal government expenditures have been increasing at a faster rate than their revenues.

- Provincial/territorial governments have seen the highest average annual growth rate in revenues.

- Federal and provincial tax revenues, per capita, increased over the 16-year period while municipal tax revenues remained fairly flat.

- Federal and provincial/territorial governments rely on personal and corporate income taxes and consumption taxes, along with other tax and non-tax revenues. Some provincial governments (including Ontario) also levy a property tax. Municipal governments rely mainly on one tax - the property tax.

- A greater increase in provincial property taxes for education and relatively smaller increases in municipal property taxes "suggest some crowding out of municipal tax room by the provincial property taxes…"6

- Municipalities do not have revenue-raising tools to allow them to adequately meet their responsibilities.

- Cities do not have sufficient control over their own destinies and are constrained from solving their own fiscal problems.

Focus of LRFP III

The focus in this third LRFP is on improving the City's financial sustainability, including the strategies and policies that need to be implemented to achieve long-term stability. As directed by Council, LRFP III gives an overview of the factors that influence the City's financial situation and outlines strategies the City will need to consider to become financially sustainable in the long-term and provides a forecast of the operating pressures facing Ottawa over the next four years and the capital requirements over the next 10 years. It also provides options for City Council's consideration for the short- and medium-term. The LRFP offers a framework to help develop future budgets and frame discussion with other levels of government and the community.

This document will provide Councillors with the information they need when setting term-of-Council priorities. It will also guide the City's financial development over the next four-year term-of-Council. The document will be updated at the end of the four-year term or earlier, if there are significant changes in the City's financial situation.

Defining financial sustainability

There are many definitions of financial sustainability, but for municipal government purposes, the definition used by the Local Government Association of Australia is the easiest to understand and the most comprehensive. The Association's definition of financial sustainability is:"…a government's ability to manage its finances so it can meet its spending commitments, both now and in the future. It ensures future generations of taxpayers do not face an unmanageable bill for government services provided to the current generation."12

Using this definition, a municipality's long-term financial performance and position are sustainable when planned long-term service and infrastructure levels and standards are met without unplanned increases in rates or disruptive cuts to services.

A municipality would be considered financially sustainable if the following conditions were met:

- There is a reasonable degree of stability and predictability with respect to taxation;

- Future generations will not face massive decreases in services or unreasonable property tax rate increases to deal with items deferred from this generation;

- The current generation does not bear all the burden of funding items that will benefit future generations; and

- Council's highest priority programs (both capital and operating) can be maintained.

In the last two years, City staff have used a balance beam analogy when presenting the City budget to describe how yearly revenues must equal yearly expenditures. The balance beam analogy also applies to discussions about financial sustainability. To achieve a balanced budget, both sides of the balance beam require adjustment. Every year, some expenditures must be reduced or eliminated and new revenues found to accommodate changes to the individual components that comprise total expenditures and revenues.

The following graph shows the balance beam for a single budget year and includes these expenditure items:

- Council-controlled services (e.g., fire, libraries, contributions to capital)

- Legislated services (e.g., employee and financial assistance, paramedics, housing)

- Boards and authorities (e.g., police services)

- Debt servicing (i.e., fixed repayments for previously issued debt)

The revenue items include:

- Taxation derived from property assessment

- Government grants and subsidies (conditional or unconditional)

- User fees (e.g., water consumption fees, recreation fees, transit fares)

- Other revenue (e.g., interest earnings)

As each component in the balance beam is subject to long-term fluctuations, organizations that are sustainable over the long-term try to smooth the adjustments required to remain in balance from year to year. One of the ways to accomplish this is to ensure that benefits received today are paid today and that expenditures are not deferred to future generations. This is referred to as inter-generational equity.

The following balance beam demonstrates how financial sustainability should look in a municipality. The expenditure side of the beam would list costs already found in the operating budget (Council-controlled services, legislated or mandated programs, boards and authorities, debt servicing). Longer-term liabilities (costs that will be incurred in the future from actions taken today) and the value of assets consumed during the period (depreciation) would also be added. To offset any increases on the expenditure side, either the existing sources of revenue are adjusted, other expenditures are eliminated, or new sources of revenue are identified.

How LRFP III fits into the City's integrated planning framework

When the first and second LRFPs were presented to Council, the City had not yet developed an overall, integrated planning framework. As a result, these documents became the strategic plans instead of the financial and funding strategies to support longer-term strategic business plans.

Council directed staff to prepare comprehensive planning documents, including a City Corporate Plan, to help set priorities for City spending.

The City Corporate Plan identifies Council priorities and establishes high-level actions and ongoing activities that the City will undertake to work towards delivering those priorities. Each action has a budgeted amount, which is included in the revenue forecasts provided in this LRFP.

The primary point of reference for the City's integrated planning processes is its strategic vision - Ottawa 20/20. Using the City Corporate Plan, Council establishes its priorities for how far and how fast it wants to move towards the Ottawa 20/20 vision. Those priorities must be established within a realistic financial context. Long-Range Financial Plan III outlines the City's financial condition and gives Council the financial context needed to set priorities.

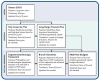

The LRFP III also outlines longer-term financial strategies that, if successful, would allow Council to advance its priorities and move towards financial sustainability. Term-of-Council budget directions will be developed to guide the formation of the budget each year. Additional detail on achieving Council's priorities is provided in documents such as departmental strategic frameworks and the operating branch narratives presented in the Budget. The actual 2007 Budget will not be provided for Council consideration until early 2007. This graphic shows the linkage between the various documents in the Integrated Planning Framework.

Linkage with the annual budget process

As directed by Council, the City will provide operating and capital budget amounts for the upcoming year, early in 2007, that include a further three years of operating and nine years of capital forecasts. This will allow Council to see the longer-term impact of decisions made as part of the City Corporate Plan and LRFP approval process.

Actions approved in the City Corporate Plan are included in the operating and capital budget estimates, and the amounts included in those estimates are consistent with the forecasts provided in this LRFP. The forecasts for years two to four of the multi-year budget documents will be updated annually to account for any significant changes in assumptions and conditions. Each update will include a four-year budget forecast.

LRFP III outlines the options for Council consideration to continue providing a good quality of life for Ottawa residents while striving to keep property taxes at a reasonable level.

12Local Government Association Financial Sustainability Program, Australia