Other sources of revenue

While expenditures tend to increase year over year across all categories, the same is not true for revenues. The City must look beyond taxation and user fees to other sources of revenue, such as interest earnings and dividends, to help fund its programs. However, Council does not control the direction of interest rates and dividends. The City of Ottawa also generates revenue from dividend payments from Hydro Ottawa and the Rideau Carleton Raceway. Other sources of revenue constituted 1.64% of the total revenue in 2005; without these other revenue sources, taxes would have increased $33 million or 3.5%.

Interest earnings

The City's main non-tax or user fee revenue comes from interest on funds not immediately required for use. Municipal Act regulations establish the investments the City can undertake, which tend to be a relatively conservative mix.

While the types of investments the City can make are limited, it is still important to maximize returns through benchmarking with other municipalities. Benchmarks include:

- ONE Fund - municipal pooled investment program designed specifically for the Ontario public sector, overseen by the CHUMS Financing Corporation and Local Authority Services Limited.

- Scotia Capital Three-Month Treasury Bill Index - composed of three-month Canada treasury bills, which are rolled into new bills at each Government of Canada Treasury bill auction.

- A composite of the Scotia Capital All Governments Short-Term and Mid-Term Bond Indices - consists of federal, provincial and municipal bonds with remaining effective terms greater than one year and less than or equal to 10 years.

While none of these benchmarks precisely reflects the investment policy, or the City's goals and objectives, they serve as a reasonably acceptable basis for comparison. The table below compares City and benchmarks returns.

Comparison of investment performance

| Returns (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200137 | 2002 | 2003 | 200438 | 2005 | |

| City - All funds39 | 4.77 | 4.22 | 4.24 | 4.34 | 3.45 |

| Scotia Capital Indices (SCI)40 | N/A | 4.09 | 3.63 | 4.26 | 3.17 |

| ONE Fund 41 | 4.38 | 3.63 | 3.61 | 3.66 | 2.27 |

| City exceeds SCI | N/A | 0.13 | 0.61 | 0.08 | 0.28 |

| City exceeds ONE Fund | 0.39 | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.68 | 1.18 |

The current legal framework within Canada limits municipalities' ability to manage and regulate the programs and services they deliver. In the United States and Europe, considerable effort has been made to allow cities to determine which services to provide and how to fund them.

Comparison with other jurisdictions

In recent years, provincial governments across Canada have provided municipalities with additional authority to raise new revenues or have transferred to them portions of their income or gas tax revenues. Although the Province of Ontario has made headway in providing municipalities with a portion of their gas taxes, it must make additional funding sources available to restore municipal fiscal sustainability.

The following table compares the municipal revenue sources in the United States and Canada.

Municipal fiscal authority: Canada and the U.S.A

| USA | BC | Alberta | Manitoba | Quebec | Nova Scotia | Ontario | Other provinces & territories | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Property tax | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Sales tax | x | x | ||||||

| Hotel/motel tax | x | x | x | |||||

| Business tax | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Fuel tax | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| License fees | x | |||||||

| Income tax: individual and corporate | x | x* | ||||||

| Development charges | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Tax-exempt municipal bonds | x | x | ||||||

| Tax incentives | x | |||||||

| Grants to corporations | x | |||||||

| Borrow money | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

*Note: Available to Winnipeg

Source: Federation of Canadian Municipalities

37For 2001, only Money Market returns are shown.

38As of 2004, City's returns are shown on a total market return basis.

39City returns are shown on a book basis prior to 2004.

40SCI portfolio management fees and expenses have not been deducted.

41ONE Fund returns are shown after incurring investment management expenses.

Taxation

Economic and policy experts agree that Canada's cities lack the legislative and financial tools needed to fund the services and programs they must deliver. They also agree that rectifying this situation is essential for Canada's economic prosperity.

This situation has been an ongoing concern for the City of Ottawa and for Canada's other large cities. Until the inadequacies of the fiscal framework are addressed, no Canadian city will be sustainable in the medium- to long-term, no matter what it does to reduce its own costs or increase its own revenues.

As experts Enid Slack and Richard Bird noted in May 2006:

"Owing to the limited and relatively inelastic revenue base to which even the largest cities have access, the underlying basis of Canada's urban prosperity is being eroded, with potentially damaging implications for national well-being over the long run."20

There are only three funding tools available to cities - property tax, user fees, and development charges - and property tax is the only tax available to municipalities. Property tax has:

"characteristics that make it different from other taxes… [It] is an inelastic tax… because property values do not grow as quickly as do incomes and sales during a period of economic growth…Even when they do grow quickly….most municipalities are forced to reduce tax rates when property values increase so that taxes do not increase by the full amount of the increase in the tax base".21

Experts agree City revenues are inadequate

It is generally agreed that "property tax has insufficient revenue-generating capacity to meet increased expenditure needs."22

Moreover, as Enid Slack notes:

"… the ability of municipalities to increase taxes and user fees is different than the ability of federal and provincial governments to increase their revenues for at least two different reasons. First, municipalities are constrained by provincial governments in terms of the services that they are mandated to deliver, on the one hand, and the restrictions on revenues they are permitted to levy, on the other hand. Second, the unique characteristics of the property tax make it more difficult to increase than income and sales taxes."23

Ontario municipalities are further disadvantaged by having to fund income redistribution programs from the property tax base. Studies show that Ontario's decision to download social services to municipalities "mak[es] no real sense."24

Studies also note that many municipalities appear, on the surface, to be quite healthy because they do not run deficits and do not borrow excessively. However, unlike provincial and federal governments, cities are prohibited from running deficits, and the amount municipalities are allowed to borrow is limited by provincial governments.

Experts agree that "the required balance has been achieved in large part by under-investing in infrastructure and service delivery."25

"Expenditures up; transfers down; and hard-to-increase own-source revenues: it sounds like a prescription for a fiscal crisis. It is thus not surprising that there has been much concern with the fiscal sustainability of cities in Canada in recent years."26

"The only way [municipalities have] to achieve a balance between revenues and expenditures, however, is by reducing expenditures or by raising property taxes. Neither prospect bodes well for meeting the economic and social challenges… facing large cities and city regions."27

Studies reaffirm the conclusions and recommendations brought forward in the City of Ottawa's first LRFP:

- Ontario municipalities should not be funding income redistribution programs from the property tax base.

"Ontario clearly needs to rethink its assignment decisions. Social services are cost-shared between the provincial and municipal governments in Ontario. Either these costs should be uploaded to the provincial government or new revenue-raising tools should be downloaded to the municipalities."28

"Shifting funding responsibilities for all social service, social housing, and land ambulance expenditures to the provincial government in Ontario, as is the practice elsewhere in Canada, would not only assist local governments, it would make sound economic sense - all income distributional services should be the responsibility of the more senior levels of government."29

- Cities need the autonomy to make decisions that will help them be more financially sustainable.

"Cities can and should do more to help themselves. To do so, however, in the Canadian context they need first to be freed from the many inappropriate provincial constraints…which are currently preventing them from financing their services adequately or efficiently, such as the presently convoluted 'capping' system… in Ontario. Cities should be able to act independently to make autonomous decisions in their areas of jurisdiction."30

- Cities need new revenue streams to be successful and sustainable.

"Some obvious ways to restore the balance between expenditure responsibilities and revenues can be suggested. These include, for example, increasing residential property taxes, user fees and borrowing, transferring responsibility for some expenditures to the provincial or federal governments ("uploading"), transferring revenue-raising power (tax room) to municipal governments (such as an income or selective sales taxes), and transferring funds from the federal and provincial governments through conditional or unconditional grants."31

Some progress has been made on these issues. The transfer of a portion of the federal and provincial gas tax is helping Ottawa fund its public transit needs. In addition, the Ontario government has established a Provincial-Municipal Fiscal and Service Delivery Review to try to create a sustainable provincial-municipal relationship for both orders of government.

In 2001, a KPMG study found that, between 1998 and 2000, for each additional tax dollar of revenue the City generated from economic growth, 91 cents went to the federal and provincial governments and only 9 cents remained for the City itself. The study was updated in 2006 to reflect the changes in taxation that have occurred since 2005. The results show that, while the total value of taxes generated for all levels of government increased by 43%, the City's share of total taxation remained at 9%. It is clear that the City is not sharing in the increased revenue arising from economic growth. However, when factoring in the transfer of provincial and federal tax revenues to municipalities, Ottawa's revenue share increases to 11% from 9%.

Progress remains slow and small in scale. If the municipal fiscal imbalance does not change soon, Canadian cities will not be able to continue to fund existing services and infrastructure.

Ottawa depends on taxation

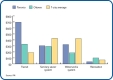

Ottawa has a higher dependence on property taxation as a source of revenue when compared to seven of the other major cities in Ontario. This is primarily due to Ottawa receiving less than its fair share of grants from other levels of government, and not being able to benefit from the pooling of social service costs like the Greater Toronto Area. In 2005, the City of Ottawa received $1.12 billion in revenue from property taxes, including federal and provincial properties that make payments-in-lieu of taxes. This represented 55.34% of the City's total revenues of $2.029 billion. Over the same period, City of Toronto taxes represented only 43.77% of total revenues. The following graph shows the reliance of the City of Ottawa on taxation compared to Toronto and the average of the other seven major cities or regions. Receiving a fairer share of the government grants would reduce the dependence of the City of Ottawa on taxation.

Analysis of revenue, 2005

The following graph depicts the property taxes on an average home in Ottawa assessed at $276,245 in 2006, compared to an average-assessed home in Toronto, Markham, Mississauga and Hamilton. The range in assessment value of the average home in each city reflects the variability in the cost of residential housing in each municipality. There is no common assessment value to represent what the average taxpayer pays in each municipality.

Ottawa's residential taxes are higher than in other cities

In 2006, the owner of an average Ottawa home paid $2,548 in municipal property taxes, excluding provincial education tax. The owner of an average home in Toronto paid $2,093 or $455 less. In 2004, the difference between the Ottawa and Toronto average municipal property tax was $515.

Taxes paid on average-assessed home

(Does not include education taxes)

Ottawa's higher taxes cannot be explained by tax increases; Ottawa residents have enjoyed the lowest cumulative property tax increase in Ontario over the last six years. The answer lies in the difference in the relative share of commercial taxes in each city.

In Ottawa, commercial properties make up 14% of the assessment base, although these properties actually account for 26% of the tax collected. Toronto commercial properties make up 17% of the assessment base, but account for 37% of the taxes collected. Overall, commercial property owners pay proportionately more of the tax share, while residential property owners pay less. Toronto has recognized the unfair tax burden on commercial properties and is moving to reduce its commercial tax ratio. This will result in Toronto's residential taxes moving closer to those of Ottawa over time.

Comparison of assessment and taxation shares

The property tax system is overly complex

Over the last eight years, Ontario has issued many tax-related acts, bills and regulations, making the tax system very complex and challenging to understand. As a result, property taxpayers in Ontario may not be truly benefiting from the principles of fairness, equity and predictability originally intended by the Current Value Assessment (CVA) property tax system. The objective of the system was to provide a more transparent, easy-to-understand property tax model (i.e., property value multiplied by the tax rate). Instead, there are components of the property tax system that are difficult to explain to residents.

Some of Ottawa's property tax challenges include: shifts within a tax class, between classes, and between regions in the province; municipal tax restrictions on some classes; lengthy capping protection for properties in certain classes; and the impact on taxpayers required to absorb capping shortfalls. Trying to explain to taxpayers how all the changes affect their taxes has been one of the biggest challenges the City of Ottawa has faced since amalgamation. All Ontario municipalities share this challenge to varying degrees.

A brief description of the issues and their impact follows.

Commercial taxes - capping and clawback

There has been much criticism about the differences between residential and commercial taxation in Ontario as well as the complexity of commercial property taxation. Commercial tax classes include multi-residential properties (low- and high-rise apartments and townhouse units), commercial properties (retail stores, banks, offices) and industrial properties (manufacturing, warehouses). Changes to municipal property taxation introduced by the Province in 1998 required municipalities to limit, or cap, any tax increases for commercial properties.

While the intent of the capping legislation was to provide predictability for commercial taxpayers, it has led to a significant problem for smaller commercial properties that now have to pay more than they should, in some instances.

Under the current capping legislation, any assessment-related property tax increase for a commercial property is limited to the greater amount of 10% of the previous year's taxes or 5% of the real CVA taxation. Assessment-related tax increases to commercial properties are limited by the capping legislation. Individual properties protected by the cap generate a "taxation shortfall" within the tax class (i.e., all properties falling in that class). This "taxation shortfall" is the difference between the amount of CVA taxes that the properties would generate and what they generate with the capping limit applied. This tax shortfall has to be recovered from other taxpayers within the class, which results in increased tax for other commercial properties.

The mechanism to recover this tax shortfall from other properties is called a "clawback." Under this process, properties that would get a tax decrease because of a reduction in assessment have the decrease reduced, or eliminated, in order to cover the shortfall. In other words, commercial taxpayers who would be entitled to a reduction in their taxes because of a reduced assessment pay additional taxes to make up for taxes not paid by other commercial taxpayers because of the capping limit.

The following table shows that, in 2005, the City of Ottawa had a taxation shortfall of $22.8 million because of capping, which was recovered primarily from smaller commercial properties that would otherwise have experienced a reduction in property tax.

| Annual taxes ($) | Clawback (More than CVA) | No adjustment (At full CVA) | Capped (Less than CVA) | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Accounts | Total Clawback ($) | # Accounts | # Accounts | Total Capped ($) | Net Benefit | |

| 0 - 200,000 | 4,014 | 15,696,669 | 3,183 | 1,853 | 5,356,322 | (10,340,347) |

| 200,000 - 500,000 | 112 | 3,550,131 | 48 | 52 | 2,680,749 | (869,382) |

| 500,000 - 1,000,000 | 7 | 1,042,781 | 2 | 4 | 2,273,315 | 1,230,534 |

| 1,000,000 - 1,500,000 | 9 | 471,815 | 8 | 6 | 630,781 | 158,966 |

| 1,500,000 - 2,000,000 | 1 | 219,993 | 1 | 3 | 351,000 | 131,007 |

| 2,000,000 - 3,000,000 | 1 | 280,008 | 1 | 4 | 1,297,170 | 1,017,162 |

| 3,000,000 - 5,000,000 | 1 | 384,034 | 2 | 7 | 5,293,268 | 4,909,234 |

| 5,000,000 - 10,000,000 | 3 | 1,180,140 | 0 | 6 | 4,943,866 | 3,763,726 |

| Total | 4,148 | 22,825,571 | 3,245 | 1,935 | 22,825,571 | |

The table also shows that the beneficiaries of the capping program are primarily commercial properties with higher assessed values.

The Province also established "the provincial threshold" for tax ratios. These thresholds were established in 1998 based on assessment values at that time. This was intended to prevent municipalities from applying any budget-related tax increases to commercial properties if the tax ratio is was higher than the threshold.

Ottawa was below the threshold until 2004. Since then, as a result of adopting tax ratios that prevent tax shifts between classes, the commercial ratio has risen above the threshold. Therefore, the City of Ottawa has only been able to impose a budgetary tax increase for commercial properties at half the rate of the residential increase for the last two years. Consequently, the other tax classes have had to absorb a greater share of the budgetary tax increase, with residential (the largest class) absorbing the biggest share.

The Province's tax policy was meant to move all properties to their full CVA. Under the capping program, there is no time limit as to when properties should be at their full CVA taxation (CVA assessment multiplied by tax rate). In each year where there is a re-assessment, progress towards full CVA taxation is disrupted because the new assessment values have to be incorporated into the scenario. The current two-year freeze in assessments recently announced by the Minister of Finance will provide some progress towards full CVA, but will not solve this problem in the longer term.

Capping was intended to move the current taxation system towards one based on CVA within a reasonable timeframe. Instead, it has perpetuated tax inequity within the commercial classes, where taxpayers entitled to lower taxes based on their full CVA taxes are denied their full reduction in order to subsidize properties with large CVA increases. Annual re-assessments were intended to alleviate large, unpredictable one-time increases of several years of incremental property values. Instead, the inequity of the capping program continues.

Residential taxation - tax shifting from other classes

In contrast to commercial taxation, for residential property taxation there are no tools in place, like capping, to reduce the impact of assessment changes. The last three assessment increases for residential and multi-residential properties have been higher than for commercial properties over the same period. The following graph shows the average increase in each class compared to the average increase across all classes for the last three re-assessments. Note that when the total assessment for a class rises above the city average, properties in the class above the average pay more tax while those below pay less.

Average assessment change in each tax year, by class

This situation first occurred unexpectedly in 2003 when there was a tax burden shift from the commercial property class to the residential class. At that time, there were no taxation policy tools available to Council to eliminate the impact of the shift. Furthermore, Ottawa was almost alone in Ontario in experiencing this type of shift and was forced to appeal to the Ontario government for mitigation tools. For 2004 and 2006, the Province temporarily allowed municipal councils to eliminate the tax shift through the use of "neutral tax ratios." A neutral tax ratio gives a heavier weight to assessment of the tax class that is losing tax so that the burden does not shift.

Residential taxes - shifting of education taxes

The last three re-assessments also created significant differences between the changes in assessment values of Ottawa residential properties and those of other Ontario municipalities. Ottawa's strong residential housing market resulted in larger average increases in assessment value than the provincial average. The following graph shows the magnitude of the differences in assessment for Ottawa as compared to the rest of the Province.

Change in average residential assessment

The Province sets residential education tax rates using assessment values from all Ontario municipalities. Given that Ottawa residential assessment values have risen higher than the provincial average, the education tax burden has shifted from other areas of the province to Ottawa. From 2001 to 2005, the City's assessment base grew 11.1% from the addition of new properties. Over the same period, education taxes increased for residential properties by 33.7%. This has cost Ottawa residential taxpayers $28 million more than taxpayers in other Ontario municipalities.

Residential taxes - inability to phase in increases

In each re-assessment, there has been significant tax shifting within the residential class as properties in some areas of the city experience much greater increases in value than others. The following graph shows the percentage of properties in urban, suburban and rural areas of Ottawa, as well as how much their taxes changed as a result of the last assessment. Generally, assessment values in the suburban and rural areas of the city are increasing at a lower rate than in the urban areas. This has been true in each of the re-assessment years. Unlike the commercial classes, the residential class phase-in is not mandatory and would be practically impossible to implement with annual re-assessments.

Tax impact of 2006 re-assessment: residential properties

Multi-residential taxes

Rental rates for apartments in Ottawa continue to increase. A portion of these rent payments contributes to property tax. City Council has always indicated a preference for a fair level of taxation between multi-residential and residential properties. The difficulty in making the comparison between the two types of properties is that the Province has determined that residential properties be valued on the sales approach (based on market sales) whereas multi-residential properties are valued on the income approach (based on cash flow from rent payments). There is no existing agreed-upon methodology for comparing the tax burden between residential and multi-residential properties.

As a result, Council has been making incremental changes in the taxation burden of the multi-residential class. Since 2001, the burden for this class has been reduced by more than $3 million, in spite of tax shifts into the class and tax levy increases. In 2000, the multi-residential class represented 6.14% of the assessment base and 11.6% of all City taxation. Today, the multi-residential class represents 6.6% of the assessment base but only 9.6% of the total tax bill. The result is that Ottawa's taxes per suite for a walk-up apartment in 2005 were $177 and $163 less, respectively, for mid- and high-rise apartments than the average for municipalities with populations greater than 100,000.32 In 2006, Council reached the 2004 tax ratio target they had set for the multi-residential tax class.

Farm taxes are among the lowest

Since amalgamation, City Council has reduced the farmland tax ratio significantly to recognize the importance of the farm sector to the City of Ottawa. In 2005, of 47 municipalities in Ontario with the farmland tax class, the City of Ottawa levied the second lowest taxes per acre - 84% lower than the provincial average taxes per acre for Class 1 farmland, and 73% lower than the provincial average taxes per acre for Class 6 farmland.33

With fuel costs rising and financial pressures increasing for the farm community, City Council introduced a Farm Grant Program in 2006. This allows farmers to defer the final payment of their 2006 tax instalment until after they have harvested their crops.

Tax mitigation tools needed

The public holds municipalities accountable for their property tax bill; therefore, municipal councils need more control over the tax and assessment systems. The types of policy tools municipal councils should have at their disposal include:

- Mitigation tools to counter the effects of large assessment increases and associated tax shifts experienced by a class during a given cycle.

- Flexibility to accelerate movement towards full CVA taxation for the classes that are currently capped.

- The ability to implement a phase-in program for residential property owners by adopting a re-assessment only every three to five years.

- The ability to set education taxes based on a levy requirement identified by the Province.

Over the years, staff and Council have provided suggestions to the Province on how to improve the municipal taxation system in Ontario. The Province has shown support for Ottawa by implementing requests for mitigation tools but the dialogue must continue to fix the property tax system

20Slack, Enid and Bird, Richard M. "Cities in Canadian Federalism." Presentation. Conference on Fiscal Relations and Fiscal Conditions. Georgia State University, Atlanta. May 2006.

21 Slack, Enid. "Fiscal Imbalance: The Case for Cities." June 1, 2006.

22Kitchen, Harry M. "Financing Canadian Cities In The Future?" May 21, 2004.

23Slack, Enid. "Fiscal Imbalance: The Case for Cities." June 1, 2006.

24Slack, Enid and Bird, Richard M. "Cities in Canadian Federalism." Presentation. Conference on Fiscal Relations and Fiscal Conditions. Georgia State University, Atlanta. May 2006.

25Slack, Enid. "Fiscal Imbalance: The Case for Cities." June 1, 2006.

26Slack, Enid and Bird, Richard M. "Cities in Canadian Federalism." Presentation. Conference on Fiscal Relations and Fiscal Conditions. Georgia State University, Atlanta. May 2006.

27Slack, Enid, Bourne, Larry S. and Priston, Heath. "Large Cities Under Stress: Challenges and Opportunities." Report. External Advisory Committee on Cities and Communities. March 3, 2006.

28Slack, Enid and Bird, Richard M. "Cities in Canadian Federalism." Presentation. Conference on Fiscal Relations and Fiscal Conditions. Georgia State University, Atlanta. May 2006.

29Kitchen, Harry M. "Financing Canadian Cities In The Future?" May 21, 2004.

30Slack, Enid and Bird, Richard M. "Cities in Canadian Federalism." Presentation. Conference on Fiscal Relations and Fiscal Conditions. Georgia State University, Atlanta. May 2006.

31Slack, Enid. "Fiscal Imbalance: The Case for Cities." June 1, 2006.

32BMA Management Consulting, "Municipal Study," 2005, p. 127.

33BMA Management Consulting, "Municipal Study," 2005, p. 172.

User fees and charges

Under the Municipal Act, municipalities have broad authority to impose fees or charges for any activity or service they provide. While municipalities can determine which services to charge for, the amount of the fee and who pays it, the Municipal Act limits them to cost recovery - in other words, municipalities cannot charge more than it costs them to provide a service.

The main user fees in Ottawa are transit fares, water rates, sewer surcharge, and registration and entry fees for recreation programs and facilities. User fees and charges directly fund a portion of the program or service costs. Since 2004, user fees have increased annually as the City strives to maintain a constant cost-to-user fee ratio. In 2005, the City collected $484 million in user fees and charges. By passing all or a portion of cost increases on to users, the City can take pressure off the residential property tax bill.

A comparison of user fees on a per capita basis is provided in the graph below.

Comparison of user fees and charges, per household

With the second largest transit ridership levels in the province, Ottawa collected approximately $115 million in transit fares in 2005, covering 37.5% of total transit expenditures, including contributions to capital. The 2005 Ontario municipal average for transit revenues as a percentage of expenditures was 42.9%. Last year, Council adopted a policy to recover 55% of direct transit expenditures from the users, thus bringing Ottawa closer to the provincial average and covering increasing expenditures. Ottawa is not unique. All Ontario municipalities have had to increase their transit user fees due to economic factors, such as higher gas prices.34

In 2005, water rates and sewer surcharges totalled $64 million and $102 million, respectively. For an average household, this amounted to $645 per year, up $53 from the previous year. The average municipal cost in Ontario for water and sewer services in 2005 was $665, up 19% from 2004. The City of Ottawa and most other municipalities across Ontario have increased user fees for water and sewer services to protect public safety, ensure infrastructure reliability and meet provincial obligations.

User fees for recreational services totalled $35 million in 2005, representing 35% of total expenditures for the service.35 While taxes still cover 65% of the cost of recreational services, Ottawa collects more user fees for this category than Toronto and the seven-city average on a per capita basis: $100 per household for recreational fees compared to $66 for the Ontario seven-city average and $37 for Toronto. The City has ensured that low-income families are not priced out of recreational programs by increasing the amount of subsidy by an amount equivalent to any user fee increase.

In implementing the user-pay principle, the City has also moved garbage collection from the assessment-based tax bill to a flat user fee for both residential and multi-residential properties. The user fee for garbage collection is part of a larger strategy to increase awareness of the cost of garbage and ultimately increase recycling rates. By removing this cost from the property tax system, commercial and industrial properties that do not receive the service from the City no longer have to pay for it.

New user fees and charges

In 2005, the City identified a number of revenue opportunities, including new user fees, for the Province to consider as part of the new City of Ottawa Act. The City was not given any of these revenue options, but the Province indicated it would study them further in its review of the Municipal Act. At the time of this report, Bill 130, the Municipal Statute Law Amendment Act, has already undergone first reading. However, the amendments to Bill 130 do not include any new financial tools.

Funding from other levels of government has declined

As discussed previously, the City receives funding from the provincial and federal governments, mostly for cost-shared social programs. Since the early 1990s, successive federal and provincial governments have balanced their budgets by downloading services or reducing funding support to municipalities. Several grant programs slowly disappeared during the 1990s, including transit and road services grants, and unconditional grants that provided general funding to help municipalities reduce the cost of providing local services.

In 1998, the Province introduced a provincial-municipal service realignment, which was promoted as "revenue neutral." The Province harmonized education tax rates during the same period and introduced a province-wide education tax rate, which resulted in lower education costs on residential tax bills. However, more services and costs were downloaded to municipalities during that exercise to be added to the municipal portion of the tax bill. Over the years, governments have further reduced the level of funding for these downloaded services.

For example, in 1997, provincial grants covered 77% of Ottawa's total social assistance spending. By 2005, these grants were reduced to 54% of the total costs. In 2001, provincial grants funded almost 31% of total social housing expenditures. By 2005, this had decreased to 24%.36

As a result of the changes to social housing grants, the waiting list for subsidized housing in Ottawa has increased dramatically and the City does not have the funding to handle the extra demand. As of December 31, 2005, 9,922 applicant households were wait-listed, meaning that about 23,000 Ottawa residents face an average waiting period of five to eight years for subsidized housing.

Increased service responsibilities, coupled with reduced funding, have presented municipal councils with challenges in balancing community needs with maintaining reasonable levels of taxation. In many cases, maintenance of city infrastructure has been deferred to achieve a balance between these competing objectives.

The good news is that, starting in the late 1990s, a number of federal and provincial programs were launched to address capital infrastructure requirements. These programs help municipalities fund critical infrastructure and meet community infrastructure growth needs. Programs such as the Canada-Ontario Infrastructure Works program (COIW), Transit Investment Partnership (TIP) and SuperBuild have greatly assisted municipalities in addressing deficiencies in their road, transit, sewer and water systems.

However, although well intentioned, these programs are short-term and require renewal. Many of them restrict how funds are to be used and, most importantly, do not provide base funding on which municipalities can rely each year. In addition, as governments change, so do priorities and funding commitments. Consequently, such programs cannot be considered sustainable and predictable sources of funding that allow municipalities to properly plan and manage their capital and operating responsibilities.

In response to the Province's 2006 spring budget, the Association of Municipalities of Ontario (AMO) President, Roger Anderson, stated: "One-time funding announcements help with the symptoms of downloading - but they do not protect the municipal property taxpayer from the ongoing burden of downloaded provincial costs." Although this type of funding benefits municipalities, it fails to address the urgent need to restore fiscal sustainability to municipal governments in Ontario.

34BMA Management Consulting Inc., "Municipal Study," 2005, pp 73-74.

35FIR 2005.

36FIR 1997, Regional Municipality of Ottawa-Carleton, 2001 Ottawa, 2005 Ottawa